Shap Local History Society met in the Memorial Hall and were welcomed by secretary Liz Amos who introduced Jean Scott-Smith the Vice Chairman who was speaker for the evening. This was the fourth and final talk in a series that have looked at the development of Shap. Mrs Scott-Smith’s subject was ‘Smoke over Shap’ about the coming of the railway; this was an extended version of her talk given to Cumbria Local History Federation conference in November 2016

Beginning with the birth of the railways in general, the audience were taken on a journey through the development of lines, and the demand for a direct route overland to Scotland. Once the railways had reached Preston in 1838 the link to Scotland became more vital, as at that time travellers had to embark at Fleetwood, also known as North Euston to undertake a long and hazardous sea voyage to Ardrossan lasting 27 hours. The next section to be completed in 1840 was the Preston to Lancaster Junction, and then an Act of Parliament was passed for the building of a railway between Lancaster and Carlisle.

Various routes were proposed, two by George Stephenson that would have seen a barrage or two viaducts across Morecambe Bay and the line following the Cumbrian coast before turning east from Maryport to Carlisle. Another proposed by the great designer Joseph Locke to go up and over Shap Fell, an idea that as ridiculed by many, this would then have gone down the Lowther valley via Shap Abbey, Bampton, Askham and Yanwath to Penrith; he also designed an alternative route from Lancaster up the Lune valley to Tebay then via Sunbiggin Tarn and Kings Meaburn, Cliburn and Eamont Bridge to Penrith. Another surveyor, George Larmer suggested a route from Tebay through Orton, Sleagill and Clifton.

There was some objection to the Shap route from Cornelius Nicholson, who saw Kendal being by passed, and who owned a paper mill at Burneside; he wanted the railway to pass through Kendal, to Burneside then up the Long Sleddale valley and by tunnel under Gatescarth pass, down the side to Haweswater to Bampton then via Lowther to Penrith. Both this route and one of Locke’s that passed close to Lowther Castle were fiercely opposed by the Earl of Lonsdale.

The designer of the chosen route that runs almost directly north from Shap Fell was Joseph Locke, who had also created a railway town of Crewe. He was one of the ‘great triumvirate’, the three young engineers who pioneered railway building; the other two being Robert Stephenson, son of George and Isambard Kingdom Brunel; all died between the ages of 53 and 56 years of age having worked themselves to death.

Thomas Brassey was the greatest contractor the world had ever known, and he was in charge of up to 10,000 navvies. He was described as the epitome of a good employer, he was well respected and treat his workers well and paid fair wages for hard work. He avoided strikes and settled grievances on the spot. The first sod was cut on Shap fell in July 1844, and first permanent rail laid in the November of the same year.

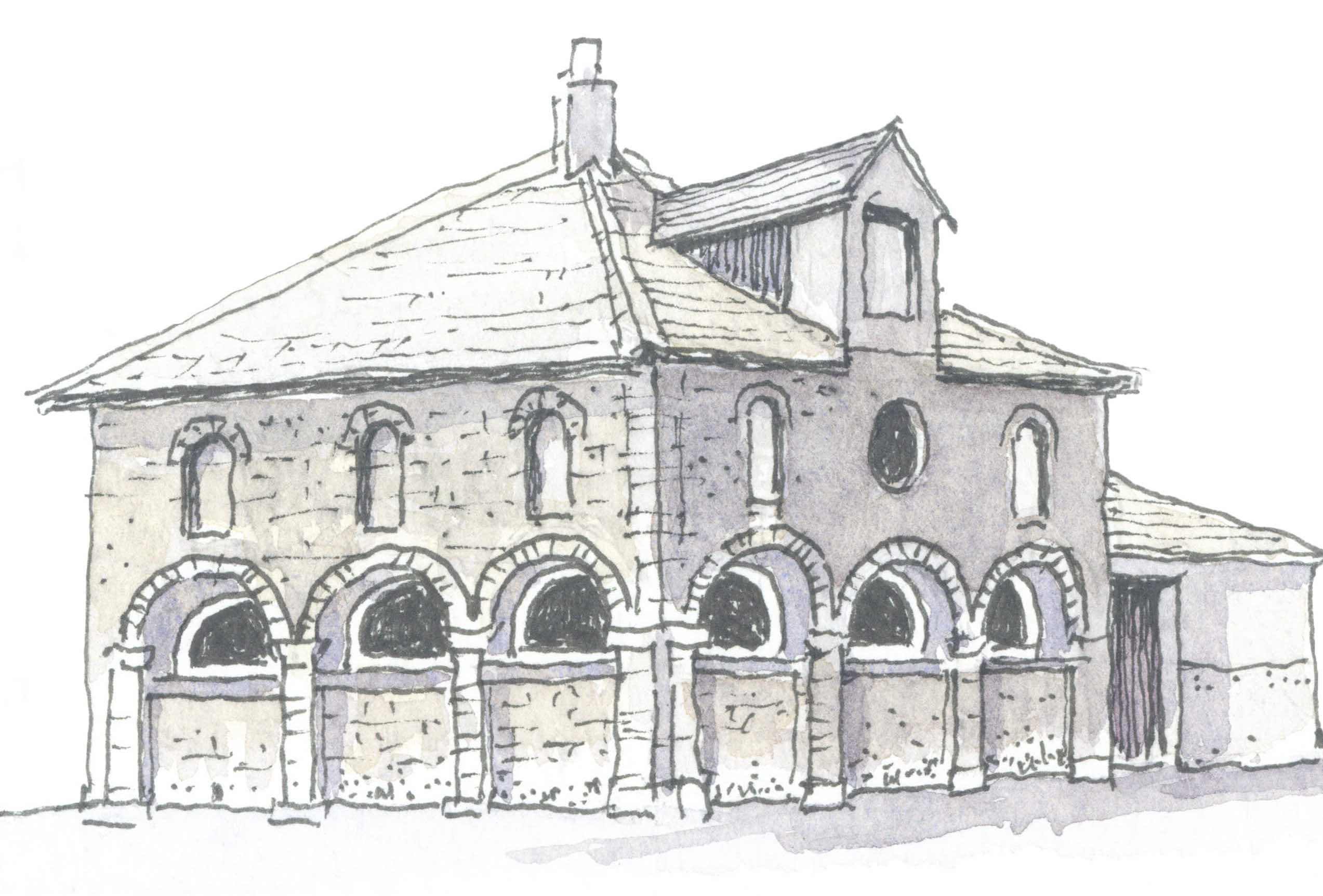

Brassey build a village to accommodate the navvies, this included a chapel and school, and huts built from sods with thatched roofs; the rows were named after London streets such as Hanover Square, Regent Street and Strand, an etching from the Gentleman’s Magazine is the only known image of this community. He was skilled in handling men and avoided fighting by keeping the Scottish, Irish and English groups separate. The men were paid once a month and spent a large portion of it on booze. Shap parish registers record baptisms, marriages and burials for the period and there is a memorial in the churchyard to those who lost their lives during the construction.

The Lancaster and Carlisle Railway was opened on15th December 1846 at an expenditure of one million two hundred thousand pounds. This was a true feat of engineering, from start to finish took just less than two and a half years to construct the 70 mile section; all with the use of manpower, picks and shovels, some explosives, horses and carts. Jean commented that today a feasibility study would not be completed in that time.

There were several slides showing steel etchings from the time of the opening featuring Lancaster station, bridges, viaducts and Penrith station.

Jean then showed a number of images of engines and how they developed over time, and explained what impact the railway had on Shap. Firstly it affected the stagecoach trade as it offered easier way to travel long distances, it also ended the droving tradition because there was now a quicker way to transport livestock. The railway also impacted in the revenues of the Heron Syke Turnpike and that was abolished in 1882.

On a positive note, the railway was one of the reasons for the establishment of Shap Granite Company which had its own sidings; that company built a lot of housing for its workforce and enlarged the village population considerably. New trades started up attracted by easy transport of goods and mail. Shap became a popular holiday destination, with guest houses being established and booklets advertising Shap as having the finest air in Britain! At this point one of the iconic LMS posters was shown.

A series of images showed locomotives and trains on the line, including steam trains aided by banking engines and some famous trains such as the Royal Scot and Midday Scot, and iconic engines such as the Coronation Scot and Flying Scotsman.

Some of the men who worked for the railway included George Grayland signalman at the Shap Summit box. Jean said that her paternal grandfather had been a platelayer, and showed a gang from the 1960s. There were images of Shap station from different angles; and one of the last staff; the station closed in 1968. Jean’s maternal uncle had started as a clerk at Shap station aged 14 and worked for the railways in Cumberland until his retirement in the 1960s after 51 years, and she shared some of his stories.

The transition from steam to diesel and electrification was illustrated, and the changes of operators illustrated through the crests and logos; the final image was of a Virgin train gliding effortlessly under the summit bridge.

Jean was thanked by Mrs Amos, and there was an opportunity for questions, and inspection of several books and railway badges on display.